Along similar lines…the pi pico w has WiFi. It would be so cool to incorporate a WiFi modem on the second core and pipe it to umac on the main core. Would that work?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

More pico-mac stuff

- Thread starter quinterro

- Start date

The logical or simplest thing to do, surely is make it compatible with AirTalk? Then it pipes AppleTalk packets over UDP and Macs or emulated Macs can then talk to it. It'd be quite a challenge to use full AppleTalk though, because the AppleTalk stack AFAIK won't fit within the RAM of a Pico-Mac.Along similar lines…the pi pico w has WiFi. It would be so cool to incorporate a WiFi modem on the second core and pipe it to umac on the main core. Would that work?

However, you don't need the stack to fit within a Pico-Mac's RAM if you can add functionality to Pico-Mac. This could take three forms:

- A standard means of mapping Pico-IO (and Pico-interrupts) to the Pico-Mac 68K side. PICO IO occupies wide address space, but it's fairly sparse. A suitable scheme could compress it to e.g. 64kB of the 68K address space. Then you can write Mac code that directly interfaces with Pico-IO. For example, an app to access GPIOs or even PIOs!

- A standard means of extending the Pico-Mac emulator to provide access to additional Cortex M0+ APIs from the Mac side via traps. An obvious way to do that would be, literally defining a TRAP #n interface, one that isn't used by Debuggers, ATARI-TOS or Sinclair QL QDOS (in case one wants to run these within the Mac emulator). Most of the actual TRAPs #0 to #15 are available and it wouldn't AFAIK, clash with either of these and you only need one. Executing a PicoTrap would dispatch to some emulator host code.

- Universal binaries! A standard means of running Cortex M0+ code from Mac applications, INITs or control panels. Cdex resources define host code. The Mac side loads a reference to the resource and executes a TRAP #PicoTrap API call. Pico code takes over and runs the code in the resource pointed to by the reference. The important thing is that it's XIP code which can run from the flash (and thus doesn't need Mac RAM), and also that it's contiguous in Flash too).

Hey Snial, weren’t you working on an emulator of your own? How far along is that?The logical or simplest thing to do, surely is make it compatible with AirTalk? Then it pipes AppleTalk packets over UDP and Macs or emulated Macs can then talk to it. It'd be quite a challenge to use full AppleTalk though, because the AppleTalk stack AFAIK won't fit within the RAM of a Pico-Mac.

However, you don't need the stack to fit within a Pico-Mac's RAM if you can add functionality to Pico-Mac. This could take three forms:

- A standard means of mapping Pico-IO (and Pico-interrupts) to the Pico-Mac 68K side. PICO IO occupies wide address space, but it's fairly sparse. A suitable scheme could compress it to e.g. 64kB of the 68K address space. Then you can write Mac code that directly interfaces with Pico-IO. For example, an app to access GPIOs or even PIOs!

- A standard means of extending the Pico-Mac emulator to provide access to additional Cortex M0+ APIs from the Mac side via traps. An obvious way to do that would be, literally defining a TRAP #n interface, one that isn't used by Debuggers, ATARI-TOS or Sinclair QL QDOS (in case one wants to run these within the Mac emulator). Most of the actual TRAPs #0 to #15 are available and it wouldn't AFAIK, clash with either of these and you only need one. Executing a PicoTrap would dispatch to some emulator host code.

- Universal binaries! A standard means of running Cortex M0+ code from Mac applications, INITs or control panels. Cdex resources define host code. The Mac side loads a reference to the resource and executes a TRAP #PicoTrap API call. Pico code takes over and runs the code in the resource pointed to by the reference. The important thing is that it's XIP code which can run from the flash (and thus doesn't need Mac RAM), and also that it's contiguous in Flash too).

Thanks for asking. I was a fair way along. It's all in Cortex M0+ assembly.Hey Snial, weren’t you working on an emulator of your own? How far along is that?

- I had all the dispatch for the instruction set written.

- I have all the addressing modes written.

- I have all the condition codes handled OK. They're handled by simply saving the Cortex M0+ flags after the Cortex M0+ operation that performs an actual ALU operation. For operations that generate flag results on an M68000, but don't on a Cortex Mx, obviously I have to perform a test. Flags are in a different order, but that doesn't matter most of the time, because Branches can just be based on the Cortex M0 flags and you only need that when you transfer them to CCR or SR, in which case they're mapped by a table. Some flags don't quite have the same behaviour in M68000 vs Cortex Mx, but handling those differences is much simpler than having to explicitly evaluate each flag (e.g. in some M68000 instructions V is cleared, but not on Cortex M0, so I have to explicitly clear V too, which is 2 Cortex M0+ instructions).

- Memory mapping should work (it's a simple 2-level indirect; addresses point to a table of 256kB block pointers, 64 of them then point to actual memory addresses at flash offsets or RAM).

- I have Move, Mtst, Bchg, BClr, BSet, MoveP, Ori, Andi, Subi, Addi, Eori, Cmpi, NegX, Move SR, , Clr, Neg, Move to CCR, Move to SR implemented.

- Stupidly I got stuck on Nbcd despite the fact it's hardly used, because I started to get obsessed about the quickest implementation, given that Cortex Mx doesn't support it directly. I was trying to be too clever by handling both nybbles at once. I should have figured out how many clock cycles I have free and just implemented nybble ops at least as fast as that.

- I haven't implemented: Tas, Illegal, Link, Unlk, Movem to reg, Lea, Chk, Scc, Dbcc, AddQ, SubQ, Bcc, Bsr, MoveQ, Divu, Divs, Sbcd, Or, Sub, SubX, SubA, TrapA, CmpM, Cmp, CmpA, Mulu, Muls, Abcd, Exg, Shifts, Rots, TrapF. Many of these have the same sort of formats I've already done, so it's not as bad as it might look.

- Testing code is so trivial, so I don't think that'll take much time... only kidding!

I think it’s interesting because I think the pico is a much better platform than a raspberry pi since you don’t have to wait for Linux to boot - it feels more like real hardware! Plus, the newer RPis seem to have gotten pretty far from the $5-$10 price point, but pi picos are still really cheap.

I just tried pico-mac on rp2040 and it’s not bad. But it would be nice to have more than a mac 128k running. The newer rp2350 has additional instructions as well as being a little faster. Had you considered targeting the rp2350 at all? If your emulator was faster, and maybe more importantly, lower ram, what kind of machine might be possible?

I wish pico-mac supported sound - it isn’t quite the same without the beep!

What’s the successor to the RP235x going to be?

I just tried pico-mac on rp2040 and it’s not bad. But it would be nice to have more than a mac 128k running. The newer rp2350 has additional instructions as well as being a little faster. Had you considered targeting the rp2350 at all? If your emulator was faster, and maybe more importantly, lower ram, what kind of machine might be possible?

I wish pico-mac supported sound - it isn’t quite the same without the beep!

What’s the successor to the RP235x going to be?

MØBius would be able to support 256kB Macs on a standard RP2040 and 512kB Macs on an RP2350.I just tried pico-mac on rp2040 and it’s not bad. But it would be nice to have more than a mac 128k running. The newer rp2350 has additional instructions as well as being a little faster. Had you considered targeting the rp2350 at all? If your emulator was faster, and maybe more importantly, lower ram, what kind of machine might be possible?

I wish pico-mac supported sound - it isn’t quite the same without the beep!

The Mythical Mac 256K!

This MacGUI blog post covers the boot process for the early System Software on a Mac 512K (or Mac 128K). In part of it, he talks about the Mythical 256KB Mac: At the beginning of the boot blocks are several stored parameters. The version number is two bytes. Another two bytes hold flags for...

68kmla.org

68kmla.org

If you build it, they will come!

Hey, speaking of ram usage: how feasible would it be to reclaim the ram ordinarily allocated for the screen? If the mac uses those 640x432 pixels as an output only (ie never reads it back), couldn’t we pipe that data to a second rp2040 that would be dedicated to running the display? Maybe a lot of work to save 34k but could it also enable a bigger screen?

Hey, speaking of ram usage: how feasible would it be to reclaim the ram ordinarily allocated for the screen? If the mac uses those 640x432 pixels as an output only (ie never reads it back), couldn’t we pipe that data to a second rp2040 that would be dedicated to running the display? Maybe a lot of work to save 34k but could it also enable a bigger screen?

Thanks!If you build it, they will come!

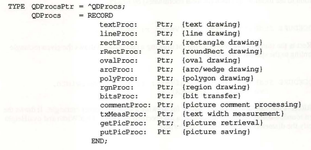

QuickDraw expects to be able to write to a memory-mapped display. Well, this is not quite true. When an app starts up, it sets up a QuickDraw variable that can point to replacement graphics primitives. It might be possible to replace those with functions that stream graphics commands and data to a second CPU.<snip> If the mac uses those 640x432 pixels as an output only (ie never reads it back) <snip>

For this system, you don't really even need much code to sit on the Mac or RP2040 host side. You probably need an INIT so that by default the pointers to the replacement routines are defined. These pointers could point to Cortex M0+/M33 code on the RP2040's flash using some kind of primitive mixed-mode manager. The actual routines grab any needed data and send the command and data to the target RP2040.

Many routines don't need much of an implementation on the host side: line, rect, rRect, oval, arc, poly, just need to send the command code and data. I believe txMeasProc and textProc can just point to the standard routines. The target would need to implement them properly, but it might be possible to hack that too, by having a Mac ROM on the target, running a rudimentary app which just picks up the data stream and translates it into equivalent commands.

An RP2040 dedicated to a Mac display can cope with far more than 640x430. 1440 x 900 could be done easily (162kB), or classic Portrait monitor sizes could be done. Having said that, it might be better to limit it to half the RAM so that when the data is picked up, it can be transferred offscreen and then target QuickDraw routines used to complete the operation. Still, 1024x768 would still be possible on an RP2040.

Yea, it sounds kinda complicated.Thanks!

QuickDraw expects to be able to write to a memory-mapped display. Well, this is not quite true. When an app starts up, it sets up a QuickDraw variable that can point to replacement graphics primitives. It might be possible to replace those with functions that stream graphics commands and data to a second CPU.

View attachment 87403

For this system, you don't really even need much code to sit on the Mac or RP2040 host side. You probably need an INIT so that by default the pointers to the replacement routines are defined. These pointers could point to Cortex M0+/M33 code on the RP2040's flash using some kind of primitive mixed-mode manager. The actual routines grab any needed data and send the command and data to the target RP2040.

Many routines don't need much of an implementation on the host side: line, rect, rRect, oval, arc, poly, just need to send the command code and data. I believe txMeasProc and textProc can just point to the standard routines. The target would need to implement them properly, but it might be possible to hack that too, by having a Mac ROM on the target, running a rudimentary app which just picks up the data stream and translates it into equivalent commands.

An RP2040 dedicated to a Mac display can cope with far more than 640x430. 1440 x 900 could be done easily (162kB), or classic Portrait monitor sizes could be done. Having said that, it might be better to limit it to half the RAM so that when the data is picked up, it can be transferred offscreen and then target QuickDraw routines used to complete the operation. Still, 1024x768 would still be possible on an RP2040.

I’ve also been looking at the rp2350 a bit more, and it supports external PSRAM (up to 32MB).

There is some throughput info here: https://forums.raspberrypi.com/viewtopic.php?t=386630

I wonder what the speed hit would be if you tried to use PSRAM, and if you could be clever about how it was used

Oh, I was trying to say it was actually feasible, because at first I was thinking that video memory had to be memory-mapped on a Mac Plus and therefore since you can't memory-map the SRAM of a second CPU, then you wouldn't be able to have a larger display. In reality, you can substitute different QuickDraw functions. However, not all software would work: software that reads and writes the frame-buffer directly would fail, only software that goes through QuickDraw would work.Yea, it sounds kinda complicated.

Secondly, to do this you need software on the host and target side - most likely software that transfers data via SPI (or a PIO-driven QSPI interface). For most QuickDraw functions on both host and target, these functions would be trivial: they just wrap up the parameters and precede them with a command code, then unwrap them on the target side.

Thirdly, I thought of a way to simplify the target side without having to rewrite QuickDraw! You make the target RP2040 also a Mac emulator, except this time it's running a dedicated program, one that simply picks up commands from the host and gets QuickDraw to draw them on a larger screen.

But thinking about it again, there might be at least 2 simpler ways on the RP2040. The first is to make use of the memory mapping technique on MØBius. By default it's a table of pointers to actual RAM or I/O routines, on 256kB boundaries. So, one could change ScreenBits in the emulated Mac's global variables to make it point to a 256kB block containing an alternative frame buffer. However, reads and writes to this area instead read and write from/to a PICO (or PSRAM) over a dedicated PIO QSPI port. It'd be slow, but again you could cache some of the Frame buffer in normal RAM, e.g. by using 16kB of what's normally the frame buffer. Then either you'd have the other PICO scanning that frame buffer and displaying it, or a task on the second CPU scanning it and displaying it.

Anyway, that's simpler, because you're not implementing a kind of Quickdraw interface. But, to emphasise, it'd be slow!

As a general software design principle it's better to start with something simpler to get it to work and then enhance it.<snip> rp2350 <snip> external PSRAM <snip> throughput info here: https://forums.raspberrypi.com/viewtopic.php?t=386630

This means that you'd still want an initial implementation which uses the XIP region to run the emulator from flash and emulate a 512kB Mac - which is a useful computer!

Supporting PSRAM would be more complex. I'd move the emulator to run from the normal RP2350 RAM, then the XIP area (which is cached in 16kB of RAM) could be dedicated to Mac RAM. You'd still want an indirect block table, because you need to handle both RAM/ROM and memory-mapped I/O, but I'd probably change it to 64kB blocks (you need 256 entries then instead of 64). Then I'd make the bottom 448kB map to the bottom 384kB of Mac RAM and the next 64kB I'd map to the normal Mac frame buffer (ScreenBits) which is always near the end of RAM. Then the rest of RAM up to 4MB, which is the maximum RAM a compact Mac can have, would be mapped to the QSPI interface. The top 72kB of RP2350 internal RAM is for the emulator and other housekeeping, which should be OK.

The XIP interface is a cache. It's 2-way set associative with 8-byte cache lines. In an emulator, emulated RAM accesses take up the minority of the memory accesses. For example, a 150MHz RP2350 could emulate a 7.5MHz Mac, so the bandwidth is roughly 3.75MB/s or 1.875M accesses/s. So, only 1.875/125=0.0125, or 1.25% of the time we're accessing RAM.

This doesn't sound like much, but uncached access are slow, I think I've read elsewhere, they can be up to 75 PICO clock cycles. And if, say, the 16kB of XIP cache handles 95% of all accesses, then we get an effective access time of 0.95+75*0.05=4.7 cycles. In turn, this slows the emulator to 0.9875+0.0125*4.7=1.046. OK, so it would make the emulator about 4.6% slower. That's probably OK.

However, it's still better to work on the initial version before trying to enhance it with 4MB support.

OK, I've done a bit of work on NBCD timing. NBCD Dn takes 6 cycles (2 internal) and NBCD <ea> takes at least 8c more for a 4 cycle fetch. This means the RP2040 version needs to be: (4/6.5+2/7.5)*125=110 RP2040 cycles at 125MHz. On MØBius, InstructionFetch+ExtraInsDecode+SrcDn+Dst.Dn(BL) will be 40 cycles, leaving 70 cycles for the actual instruction execution. This means I don't need an efficient routine to be faster than a real Mac. I estimate my routine might take 20 cycles overall, so it'll run at the equivalent of a 11.9MHz Mac.Thanks for asking. I was a fair way along. It's all in Cortex M0+ assembly.

- Stupidly I got stuck on Nbcd despite the fact it's hardly used, because I started to get obsessed about the quickest implementation, given that Cortex Mx doesn't support it directly. I was trying to be too clever by handling both nybbles at once. I should have figured out how many clock cycles I have free and just implemented nybble ops at least as fast as that.

SBCD and ABCD are slightly different. Dn,Dn operations also take 6 cycles, but InstructionFetch+ExtraInsDecode+Src1Dn+Src2Dn+Dst.Dn(BL) will be 53 cycles leaving 57 cycles for the actual instruction. A bit tighter, but I still don't need them to be efficient to be faster than a real Mac.

I wonder if it's worth contacting the guy who wrote PICO-Mac and see if he's interested in a collaboration?

Thirdly, I thought of a way to simplify the target side without having to rewrite QuickDraw! You make the target RP2040 also a Mac emulator, except this time it's running a dedicated program, one that simply picks up commands from the host and gets QuickDraw to draw them on a larger screen.

That’s really a brilliant idea - it was the rewriting QuickDraw that was sounding like a lot of work. Aside from enabling a larger screen, you’d eventually be able to use the rp2350 hstx to do DVI

But I agree with your sentiment of getting the simplest thing working first.

It would be! There's something called the Macintosh Application Environment, which has a compiled version of QuickDraw though.That’s really a brilliant idea - it was the rewriting QuickDraw that was sounding like a lot of work.

Pretty sure it won't fit on an RP2040 though.

I only know about RP2040 doing VGA, but PIOs are clever.Aside from enabling a larger screen, you’d eventually be able to use the rp2350 hstx to do DVI

Well, I think I've done NBCD now. I've estimated the timings for the Dn rather than the Memory accessing case, though my implementation covers both. Ironically, although you'd think the register case is the simplest and fastest, in fact relatively-speaking it's the slowest and most critical. That's because Instruction decode and effective address decode (including the Dn mode) is slow, leaving relatively little time for the execution phase, but reading and writing memory locations is much faster than the 4x6.5MHz cycles real M68000, even with address translation. So, if the Dn mode is fine, then the Memory accessing modes will be fine.But I agree with your sentiment of getting the simplest thing working first.

Final timing:

that means 4 cycles at 6.5MHz + 2 cycles at 7.5MHz = 0.88us = 110c on the RP2040 at 125MHz.

InsFetch+ExtraInsDecode+SrcDn+Dst.Dn(BL) will be 40c, leaving 70c for the Execution phase.

Execution Phase (X=n means the M68000 X flag=n on entry):

X=1 case: 27c/28c (Full total= 67c/68c, equiv=10.7MHz/10.5MHz Mac)

X=0, no lower nybble carry, 31c/32c. (Full total =71/72, equiv=10.1MHz/9.9MHz Mac )

X=0, lower nybble carry, no upper nybble carry: ^^+3 = 34c/35c (Full total=74/75, equiv 9.7MHz/9.5MHz Mac)

X=0, full carry: ^^+2=36c/37c (Full total=76/77, equiv=9.4MHz/9.3MHz).

You can see why all the cases for BCD negation make such a difference, the slowest option is 11% slower than the fastest option. Thankfully even the worst case is 43% faster than a real Mac 256kB/512kB.

With NBCD done, progress on other opcodes should be a bit faster.

Nice! So going back to the testing/validation question: how do you structure a test of the emulator core? Do you emulate the Cortex code so you don’t have to run it on pico hw?

I’d imagine there are specific tests to run, but after the emulator is passing those, would you do something like execute a randomly generated code listing and then compare the final state (flags, memory, etc) against the expected state? Perhaps obtaining that expected end state from an existing 68k emulator?

I’d imagine there are specific tests to run, but after the emulator is passing those, would you do something like execute a randomly generated code listing and then compare the final state (flags, memory, etc) against the expected state? Perhaps obtaining that expected end state from an existing 68k emulator?

I'd do the most basic testing bottom-up, so I'd test vectoring to all the different primary opcodes (which for me, means the 256 entries from the top byte). All I have to do there is check I can execute each M68000 instruction vector. I can replace each of them with a dummy routine that just goes back to the vectoring routine. The vectoring routine is small, but critical.Nice! So going back to the testing/validation question: how do you structure a test of the emulator core? Do you emulate the Cortex code so you don’t have to run it on pico hw?

Then I'd probably test memory/io fetch/store. There's 2 x 2 x 3 major cases there.

Then I'd do the same thing for the Effective Address Vectoring code, which is a 64-way dispatch. This one performs more work, but I can check the M68K and Cortex M0+ state after each one. There's D0..D7,A0..D7, (an), (an)+, -(an), d16(an), d16(pc), d8(an, rm.w), d8(an, rm.l), d8(pc, rm.w), d8(pc, rm.l) to test: 25 routines. I can probably write test cases for this.

Then I'd move onto the instructions proper, going through all the supported code paths I have.

So, when things are starting to stabilise, I think I'd probably grab tests from an existing 68K emulator and run those against MØBius.Perhaps obtaining that expected end state from an existing 68k emulator?

Then I'd run the Toolbox ROM.

In a sense it's all a bunch of filters, eliminating the most likely errors. So, by the time I arrive running the Toolbox ROM I should have eliminated 95% to 99% of all the bugs and trapping where the ROM fails or diverges from a real Mac, will reap exponential rewards for incremental improvements. I won't be able to compare the exact cycle time behaviour, because interrupts will mess up the determinism (e.g. because the interrupt rate is real-time, but MØBius will be faster than a real 68000; MØBius will be far further along in the ROM by the time an interrupt occurs).

Minor MØBius update: I've now done the next instruction: PEA (Push Effective Address). As usual for this stage of development, even single instructions can lead to a relatively large amount of development. In this case, PEA, needs an effective address, but unlike my previous EA routines, I don't want to fetch the contents (nor store them); I just want to calculate the address. This led to another set of routines, however when writing them I realised that my 'MMU' code (which isn't a real 68K MMU, it just translates from logical 68K addresses to physical addresses on the RP2040 or calls an I/O routine if it's an I/O address) had a few errors and could have trampled over some registers used by routines that call it. So, I had to go through my code to make sure that didn't happen and needed to make a few corrections.Nice! So going back to the testing/validation question: how do you structure a test of the emulator core? Do you emulate the Cortex code so you don’t have to run it on pico hw?

I’d imagine there are specific tests to run, but after the emulator is passing those, would you do something like execute a randomly generated code listing and then compare the final state (flags, memory, etc) against the expected state? Perhaps obtaining that expected end state from an existing 68k emulator?

Normally, I wouldn't need to do much of that, because I'd write functions that always push the registers I need and pop them at the end of a function. But for this emulator, given that it might well be fairly tricky to achieve at least the equivalent performance of a real 6.5MHz 68000, I use global register assignments. I have about 4 registers used as temps during instruction execution, and I do push and pop regs when I'm sure it won't violate my emulation goals, but this global register assignment will inevitably have an impact on testing.

In essence that's a real difference between a compiler and a human; though I think Clang/GCC can do global register assigns too. It's just that ARM Cortex only has 8 registers that are readily available (R0..R7) and a few instructions that can access R8..R15.

Anyway, one upshot is that I now have a rudimentary estimate for the size of the emulator core. It's going to be between 5kB and 8kB. I've done 36% of the operations so far and next up is MOVEM regs to memory. Ironically, I don't need to make this routine very efficient, because EA calculations and storing are much faster than a real 68000, about 4x faster. I could make it blindingly fast, but I'll probably keep repeatedly evaluating the EA Dest mode for every new word to be stored. I might even combine MOVEM.W regs to memory and MOVEM.L regs to memory as that'll still be far faster than the real thing. Having said that, a superfast implementation is tempting, because lots of 68K code will use movem to save and restore registers across functions, because that's what I do.

Maybe it’s too early to ask, but do you envision the emulator core following the same conventions/interface functions as e.g. musashi? So a pico-umac build could swap in MØBius as the engine? I wonder what other platforms it might also work with? I guess mame in its full form is out of scope, but I wonder if a pico could emulate 68k based arcade systems? Or pico-genesis? Just thinking out loud about how broadly MØBius might be used

I would if it doesn't compromise the performance of MØBius. There's not much point if compatibility leaves MØBius without a compelling edge over other 'C'-based emulators. I"ve looked a bit at the interface for MinivMac, PCE-Mac, Cyclone and Musashi, they're all somewhat different and incompatible with each other. Another obvious interface would be MAME (as you said later, and correctly dismissed).<snip> the same conventions/interface functions as e.g. musashi? So a pico-umac build could swap in MØBius as the engine?

MØBius is also designed to be a dual-processor emulator. If you look at MinivMac or PCE-Mac, they're both designed to run like a classic video game:

C:

void Emulator(void)

{

Init();

while(!Quit) {

float ms=millis();

CpuExe(16.7); // 1/60th of a second's of Cpu=1 frame.

VideoUpdate();

IOUpdate();

while(ms+16.7<millis())

;

}

}Obviously, this is somewhat over-simplified, a real emulator pre-calculates the number of instructions the Mac could execute in a frame or calculates the number of cycles and then the CPU emulation counts cycles more accurately. PCE-Mac and to an extent MinivMac, can subdivide emulation in shorter periods so that it can handle IO in a more timely fashion, or they can scale the CPU execution speed relative to Video and IO, which still needs to happen at actual Mac 68K rates.

The CPU interface reflects this kind of model. Some I/O is synchronous with Cpu execution, but some I/O gets stuffed into a buffer to be handled in the IOUpdate() phase. The first major problem with this kind of model as I see it is that although the overall performance can match the real performance of a Mac, execution is chunked, so the CPU's perception of real-time events doesn't and can't match the outward real-time performance.

Consider a MIDI sequencer: this is actually a problem I found when trying to get miniVMac (and later PCE-Mac) to run on a Raspberry PI and use its serial port as a MIDI interface to a real instrument.

Let's say the 68K CPU itself is only taking 50% of the host's CPU, so it's running internally 2x faster than reality. it's playing a sequence and in the sequence there's a drum-event every 10ms - OK that's ridiculously fast for an actual drum pattern. But it means that at the beginning of the first frame it sends the 3 bytes needed for the first beat, to the serial buffer and then 10ms of its time later (5ms in reality) it sends the second beat event. The third beat is sent at 20ms, which is actually 3.3ms of 68K CPU time into the next frame (1.65ms). In reality, assuming it sends data directly to a real serial device, then an event is sent at 0ms and then at 5ms, then at 16.67+1.65=18.32ms and then at 23.32ms, instead of 0ms, 10ms, 20ms and 30ms. It's worse if serial data goes to an internal buffer and then only sent out in the IOUpdate() phase. Then data is sent at maybe 5ms, 8ms, 21.7ms and 24.7ms without video updates or sometime later with video updates.

The same problem happens in reverse when it's receiving events. Let's say you've got a MIDI drum kit and you're sending an event from the kit to the Mac every 10ms and the first one happens to be at the beginning of the first M68K cycle. It'll pick up the first beat at 0ms. The second one is at 10ms, but that's after the first frame's worth of CPU emulation (which only takes 5ms), so it doesn't pick it up until the beginning of the next frame, at 16.67ms. The third one is at 20ms, 3.33ms of real-time [6.66ms of M68K internal time] and the fourth one is at 30ms, which is during the video/IO processing, so it's picked up at 33.33ms of realtime. Hence instead of 0ms, 10ms, 20ms, 30ms the internal timing is 0ms, 16.67ms, 23.33ms, 33.34ms. Playback will mess the timing up even further to 5ms, 21.67ms, 24.67ms, 38.34ms.

That kind of problem doesn't happen with MØBius, because its execution model is much closer to PowerMac emulation of an M68LC040 (except it's just emulating an M68000). MØBius runs as fast as possible and all the time, so its realtime, is realtime. Some trivial synchronous I/O processing will be emulated synchronously, but anything that requires significant background processing will be allocated to the second CPU.

But this doesn't mean that pico-umac can't work with MØBius. Instead what I'd do is modify pico-umac's emulation model to work with MØBius's interface. Or if needed, a minimal compromise between the two that doesn't sacrifice MØBius's execution too much.

You're right, MAME would be too hefty. However, MØBius is a good candidate for Sega Megadrive emulation (what the Genesis is called in the rest of the world).I wonder what other platforms it might also work with? I guess mame in its full form is out of scope, but I wonder if a pico could emulate 68k based arcade systems? Or pico-genesis? Just thinking out loud about how broadly MØBius might be used

@Argyle Gargoyle :

OK, next update: I've implemented half of MOVEM! MOVEM.W regList,<ea> and MOVEM.L regList,<ea> are now implemented.

In the end, it's partially space and performance optimised. MOVEM.W and MOVEM.L share the same main part of the code. The big concern with MOVEM compared with other memory operations is that memory has to be accessed multiple times, so there's a dilemma between multiply re-evaluating the addressing mode or just taking the physical address that I computer from my initial <ea> calculations and storing regs from there.

The disadvantages with the former approach are:

So, my <ea> code returns the address of a data/address reg or the physical address of an address in other cases. However, when storing, registers need to be stored little-endian (as regs are held in native format for performance); while memory must be stored big-endian, M68000 format.

For MOVEM.x reg,<ea>; it only works for a memory target, so I thought I'd have to duplicate my storing code just to handle memory-only operands, but it turned out I didn't: the two forms are on different code paths so I could just use a single label to access memory-only stores.

So, now the method is to get the register mask, then the <ea>; then loop and store the bitmask of regs. So normally it will be very fast: <30c per word or long word, equivalent to about 1.5 Mac CPU cycles: about 2.67x faster per word and 5.3x faster per long word. Yet, there are cases where MØBius might be slower, namely when few, later registers are stored, because there's an 8c loop per bit of the register mask. So, 15x8=120c, or 6.24 Mac Cycles. That might need a bit of further optimisation (a bit of binary subdivision). The length is OK, a total of 49, 16-bit instructions.

I also found a bug in my memory storing routine: I was using a str instruction after reversing the bytes to little-endian. That won't work on odd word-aligned addresses so I needed to substitute a pair of strh instructions.

Conclusion: MOVEM.x took quite a bit of effort and I've only completed half the instruction! At least I didn't have to rewrite or create new memory to <ea> routines to support it and it will be pretty fast!

OK, next update: I've implemented half of MOVEM! MOVEM.W regList,<ea> and MOVEM.L regList,<ea> are now implemented.

In the end, it's partially space and performance optimised. MOVEM.W and MOVEM.L share the same main part of the code. The big concern with MOVEM compared with other memory operations is that memory has to be accessed multiple times, so there's a dilemma between multiply re-evaluating the addressing mode or just taking the physical address that I computer from my initial <ea> calculations and storing regs from there.

The disadvantages with the former approach are:

- if the opcode reg gets messed up by either when calculating the <ea> or the code that finally stores into RAM, then I have to keep restoring the opcode, which will slow things.

- It's a pretty slow mechanism when we already know the address from the first <ea> decode.

So, my <ea> code returns the address of a data/address reg or the physical address of an address in other cases. However, when storing, registers need to be stored little-endian (as regs are held in native format for performance); while memory must be stored big-endian, M68000 format.

For MOVEM.x reg,<ea>; it only works for a memory target, so I thought I'd have to duplicate my storing code just to handle memory-only operands, but it turned out I didn't: the two forms are on different code paths so I could just use a single label to access memory-only stores.

So, now the method is to get the register mask, then the <ea>; then loop and store the bitmask of regs. So normally it will be very fast: <30c per word or long word, equivalent to about 1.5 Mac CPU cycles: about 2.67x faster per word and 5.3x faster per long word. Yet, there are cases where MØBius might be slower, namely when few, later registers are stored, because there's an 8c loop per bit of the register mask. So, 15x8=120c, or 6.24 Mac Cycles. That might need a bit of further optimisation (a bit of binary subdivision). The length is OK, a total of 49, 16-bit instructions.

I also found a bug in my memory storing routine: I was using a str instruction after reversing the bytes to little-endian. That won't work on odd word-aligned addresses so I needed to substitute a pair of strh instructions.

Conclusion: MOVEM.x took quite a bit of effort and I've only completed half the instruction! At least I didn't have to rewrite or create new memory to <ea> routines to support it and it will be pretty fast!

OK, next update: EXT.W dn, EXT.L dn and SWAP dn are implemented. These were both simple to do. EXT.W/L require Cortex M0+ flags to emulate N, Z, with V=0 and C=0. This takes 3 Cortex M0+ instructions, which illustrates the power of writing an emulator in assembly.

SWAP was done using 2 Cortex M0+ instructions: REV (which swaps the byte order: DCBA into ABCD) and REV16 which swaps the byte order of both bytes in each 16-bit half word ( ABCD into BADC). Thus combining these achieves DCBA to BADC, which is a word swap. I could have done: MOV rTemp,#16: ROR rD,rTemp. This is also 2 instructions, but uses 2 registers.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 29

- Views

- 8K