Sorry, I think you are confused or missing my point, perhaps I was unclear.( @Phipli ) it adds up, but there are a few reasons why I don't think that's the cause.

Firstly, there are no Read-Modify-Write memory instructions on a PowerPC, just load and store. So, this sequence of bus cycles in non-cached DRAM would have to be implemented in software, not the Capella bridge chip (load a 32-bit word to a register; insert the byte into the right position; write the long word back). But that doesn't make sense either, it would mean that the ROM had to consider the underlying PPC/'040 bridge.

Secondly, I don't think it makes sense to be implemented in Capella either. For cachable addresses, whole words get loaded into L2, then L1 cache - a block of 32 bytes (8 words) are loaded at a time and if a byte or half-word is modified there (which is now on the PPC side of course), the whole word (i.e. 8 words) would be written when the cache line needs to be flushed. So cacheable memory never needs an RMW sequence, nor a byte modification sequence.

Thirdly, from the developer note, it seems fairly clear that the interface between the 68040 bus to the PPC603 is a set of 543 latches:

So, I don't think it makes sense for Capella to emulate a byte store to uncached RAM to load an entire word into the D-latches from DRAM, then modify the intended byte, then write the 32-bit word back out. For byte loads it wouldn't matter, a PPC603 would still just load a 64-bit double-word and select the right byte.

It also makes little sense, given that the only way Capella can know if there's a non-cacheable byte write is if the PPC603 tells it. So, there are signals from the CPU for that purpose. It's far easier for DRAM to include byte line selects and simply pass those signals on. Even though the CPU will probably send out 64-bits + the byte select signals; Capella must know how to select the high or low 32-bit word, because DRAM is 32-bits wide. It must do that for normal writes anyway.

From page 8-15 it works like this:

A29-A31 (which are the low-order bits in the insane IBM convention), select the byte lane while the 3 signals TSIZ0:2 ==001, meaning 1 byte.

It's very easy for Capella to use this information to select the right byte lane in DRAM. A similar approach works for 16-bit and 32-bit read/writes:

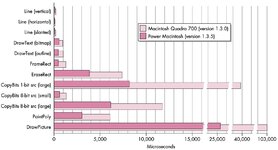

Poor Video RAM performance is, I would deduce, for other reasons.

I don't mean a read-modify-write sequence as in an instruction that causes a read-modify-write bus cycle. I don't think the 68K ROM used these as only specific instructions use them. I'm referring to the QuickDraw use case of reading a particular address (framebuffer for a particular pixel), modifying the data, then writing it back. The point of mentioning byte width (as an example for 8bpp) is that an entire bus transfer cycle is required regardless of width if the address is cache inhibited. If for each pixel changed you're doing two full bus cycles, as I said, that gets expensive quickly because you accumulate additional wasted cycles from bus translation overhead.

Edit: To further clarify, most QuickDraw accesses act like that - basic drawing instructions and the like. In some cases it's possible to do larger transfers (blits, moves, and the like) but that depends a lot on the specific request, organization of framebuffer memory, bit depth, etc. A line from A to B is going in most cases to cause a series of single-pixel changes requiring that exact read-modify-write trace (but not a RMW cycle) I mentioned above as the framebuffer is typically cache inhibited.

Cache inhibition can be a handled a couple of two ways. Most commonly it's handled by MMU flags on particular pages/portions of address space that indicate if the caches should be inhibited or not. This is how apple did it on all models of 68K mac and I would assume on PPC as well. It's possible for an external device (at least on 040) to indicate that a particular transfer shouldn't be cached, but this should only be used in very specific cases. Assuming the page is marked as cache inhibited via the MMU, on any access, the caches will not be checked nor will the result of the bus cycle be stored in cache. On an 040 this is the primary way a bus cycle of less than a line width would happen.

You want to inhibit the caches for IO devices, for example, and other circumstances where the contents of the addressed memory may change unexpectedly (DMA). In most 68K macs only the ROM and (most) main memory DRAM is cachable; nubus space and IO space is not and framebuffer lives somewhere in there.

Last edited: