That's a very nice resource. Thanks! Especially that the source code of the benchmark is there. I will try (eventually) to port it so I can run it on Mac OS on a 5200.

Once I have results will update and add it it. Probably it will be close to how the 601 performs (relative changes): 486DX2@66: +16%, +70%, +230%; P90 scaled to 66: -39%, -31%, +17%.

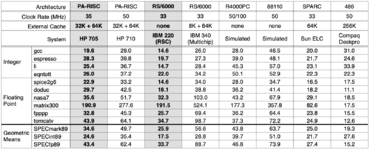

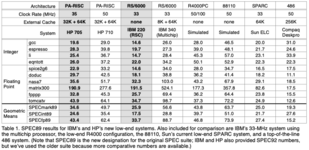

| CPU/Machine | L2 (or L3) Cache | OS | Compiler | MEM | INT | FP |

| 603e 200 MHz | 200Mhz Freescale MPC8241 linkstation (LS1) (Buffalo NAS) w/ MPC603e Motorola PowerPC core | 16KB (probably typo, this is likely L1) | Linux 2.4.17_mvl21-sandpoint | gcc-3.3.5 | 0.713 | 1.050 | 0.877 |

| 603e 180 MHz | Motorola PPC 603ev 180 MHz | 256 KB | Linux-pmac-2.1.24 | egcs-1.0 | 0.721 | 1.016 | 1.396 |

| 603e 166 Mhz | Amiga dual CPU: PPC 603e 166MHz and 68040-25MHz | 0 KB | PPC-Linux | gcc 2.7.2.1 ppclinux | 0.610 | 0.875 | 1.020 |

| P54C 90 MHz | Intel Pentium 75 - 200 90MHz | ? | Linux 2.4.28 | gcc-2.95.4 20011002 | 0.255 | 0.273 | 0.479 |

| P54C 90 MHz scaled 66 Mhz | | | | | 0.200 | 0.351 | 0.351 |

| 601 66 MHz | Apple Power MacIntosh 601 66MHz | ? | MkLinux | gcc ?2.7.2.1 | 0.122 | 0.240 | 0.410 |

| 68060 50 MHz | Amiga with Motorola 68060 50 MHz CPU | ? | Linux-2.0.36 | gcc 2.7.2.3 | 0.175 | 0.215 | 0.096 |

| 486DX2 66 MHz | Intel 486DX2 66 MHz | 256 KB | Linux-2.1.66 | gcc 2.7.2.3 | 0.105 | 0.142 | 0.124 |

Returning to this thread after several months as I missed the replies. Thanks for the comments. Good find on the links to MPR articles, as that magazine was very well respected, but had a really expensive subscription (Manchester University, UK subscribed to it when I was there).

It's interesting to note how much better the 603e did over the Pentium on these Byte benchmarks - I guess the SPEC marks operate in quite a different way. I've recently been re-reading the BitSavers architecture links on the 603e, 88110 and Pentium & thinking about why the 603e and Pentium could beat the 88110 even though the 88110 had many more execution engines (all of them are 2-issue, Superscalar CPUs and both the 603, 88110 and Pentium have 8kB Instruction + 8kB Data caches, but the 603e has 16kB caches).

An obvious place to start is to think about the most common instructions in any piece of code. One tends to find that the most basic instructions have a similar distribution:

- An ALU operation.

- A Load/Store operation.

- A comparison.

- A branch.

This means that any 2-issue superscalar CPU can achieve similar performance if they contain at least 2 execution engines targeted at these operations. The 603e has a separate load/store execution engine and Integer Unit; The Pentium appears to only have 2 ALU pipelines, but in reality both of those pipelines include the equivalent of a load/store unit, because x86 instructions have reg,mem / men, reg operations. Therefore it could be argued that the Pentium has the equivalent of 4 Execution Units in some circumstances. Finally, the 88110 also has an ALU (in fact 2) units + effectively a load/store unit (though it's integrated into the MMU and cache).

All of these CPUs have their own kinds of limitations though: the 603e only has 1 IU while the Pentium and 88110 are restricted on how they can pair up instructions.

Both 8kB cache: 32 byte line size x 2 way, same as 88110 for both caches.

88110 Features (Issue restrictions, Branch Target Instruction Cache)

As an early superscalar CPU, the 88110 has some significant issue limitations in that issue happens in-order. Both slots get stalled if the 1st slot is stalled; the 2nd slot moves to the first if it can't yet be issued, but the 1st can and only if both slots can be issued they both proceed. This means that no instruction can ever by-pass a stalled issue slot (and stalls will frequently happen due to data dependencies). In essence, it has a 2 entry reservation station shared for all units (though the branch unit also has a reservation station once it's been issued).

The 88110 implements what Motorola calls a Target Instruction Cache, which has 32 entries and each entry contains 2x 32-bit instructions + a logical address tag. Initially, they're all marked as invalid, but whenever a branch is taken, the next two instructions fetched are copied to a random, free TIC entry and marked as valid. Then if a branch at that address is taken in the future, the issue queue immediately replaces whatever was there with the corresponding two instructions from the TIC. This eliminates a branch penalty about 50% of the time, depending on whether the branch instruction itself was in the first or second issue queue slot.

In addition, the 88110 uses a static branch prediction scheme for bcnd (branch-conditional) instructions whereby backward branches are predicted taken. Finally, the 88110 can execute subsequent instructions in the instruction stream while a branch in the branch reservation station is waiting for its condition (stored in a GPR) to be evaluated and can back out of those instructions if the branch wasn't predicted correctly.

So, the 88110 can short-cut a cache fetch when a branch takes place, but it can't eliminate the branch itself.

PATC = 32 entry, BATC=8 entry.

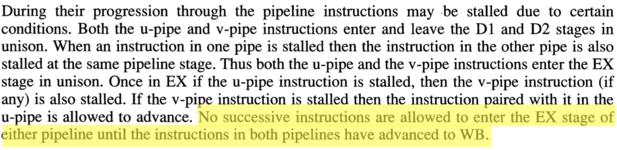

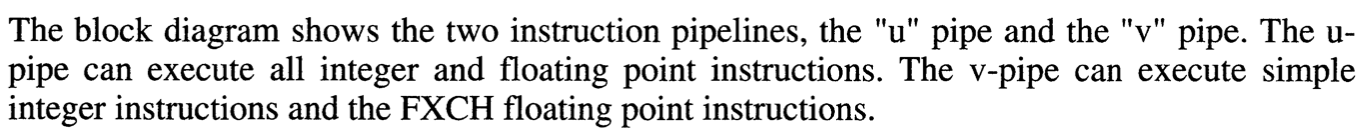

Pentium Issue & Branch Prediction

The Pentium has more severe issue limitations than the 88110. Both pipelines (U and V) proceed in lockstep where any stall in one pipeline until the EX stage also stalls the other pipeline. The EX stage however, can complete a U pipeline instruction while V is stalled in EX. In addition, both pipelines can only be used if instructions are 'simple'; with no dependancies, no displacement + immediate operands and almost always no prefixes. However, quite a lot of instructions are deemed 'simple', including most mov/alu reg,reg/mem/immediate and mem,reg instructions + inc/dec/lea/push/pop/jmp/call/jcc instructions. However, all jumps can only be paired if they're going to V.

The Pentium branch prediction uses a dual 32-byte prefetch buffer; one for sequential execution (including predicted non-taken branches) and the other (speculative) filled according to the branch target buffer once a branch is predicted taken. Both buffers are cleared once a branch has been mis-predicted.

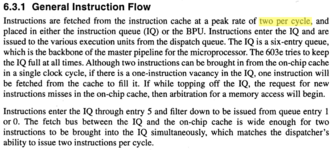

PPC603e Issue & Branch Prediction

Instruction issue is more flexible on the 603(e). The 603e has some rename registers (ctr, lr, 5x GPR, 4x FPR) and it has reservation stations for each Execution Unit (branch conditional, IU, FPU).

The PPC603(e) has static branch instruction prediction and can perform branch folding. The Branch Processing Unit decodes Instruction Queue branches prior to the dispatch stage, allowing following instructions in the 6-entry instruction queue to be issued without a branch cycle or penalty in some cases. It can speculatively execute the predicted branch instruction stream, but won't write-back results until the branch is properly completed. This avoids having to restore CPU state at the expense of periodic stalling.

The PPC603 has a few more limitations over the PPC603e: Stores have a 2 cycle latency & throughput; add & compare instructions aren't performed in the SRU (I guess they're performed in the IU).

Conclusion

It's interesting (IMHO) to compare the design decisions in these three superscalar architectures, because they all have very similar levels of performance and a similar instruction issue rate.

The biggest individual weakness of the 88110 is likely to be lack of reservation stations and rename registers: the 2 entry issue queue essentially is the reservation station. The second biggest weakness is likely to be issue restrictions and the third weakness, the branch unit placed at the Execution stage (though the branch target cache will help).

The biggest individual weakness of the Pentium is likely to be the far more serious issue restrictions than any of the RISC architectures. The second-biggest weakness is the complex pipelining in both execution engines in that register, register instructions in one pipeline will get stalled by reg,mem instructions in the other. The third biggest weakness is the lack of registers. I was thinking that the 32-byte prefetch buffer was a major weakness, but actually it's the same size as the 8-entry Instruction Queue on a PPC 601 and only 25% longer than the one on the PPC 603(e). This implies that instruction throughput is probably fairly similar.

The most critical issue in all three is likely to be the size of the caches. Even though the code density of x86 is about 33% better than PPC (according to this

paper), it's not enough to compensate for the 2x (16kB) cache sizes on the PPC603e. The most surprising aspect about the Pentium is that it can actually keep up with the other architectures, even though it needed over 2x the number of transistors as an 88110 and PPC603.

Finally, returning to the 88110. I think it's fair to say that if Apple had stuck with the 88110 and dumped the CPU/Pink OS collaboration with IBM, we could easily have had cutting-edge RISC Macs by 1992, a full year before the Pentium was released and the boost in revenue to Motorola could have kept the RISC Macs competitive until at least the end of the actual PowerPC era (though I am a substantial PPC603e fan). Another upshot could have been the emergence of Radiation-hardened 88K (rather than PPC) CPUs ending up on Mars!